Image: Karl Marx and the “King of the Jews”, Lionel Rothschild

Part II:

Revolutionary Ideology: Prioritizing Anti-Antisemitism

Karl Marx’s communist theory legitimized radical revolutionary action, yet combating antisemitism often took precedence over opposing capitalism. This is evident in his contradictory political priorities. His materialist theory of history posited that industrialized nations like Britain were primed for revolution, yet he tempered agitation there while advocating it in less-industrialized Russia. This may be attributed to Britain’s relative tolerance toward Jews, contrasted with Russia’s “antisemitism”, characterized by Pale of Settlement restrictions. In Russia, Jews faced discrimination and even violence, whereas in Britain, Jew Lionel de Rothschild rose to become the leading banker.

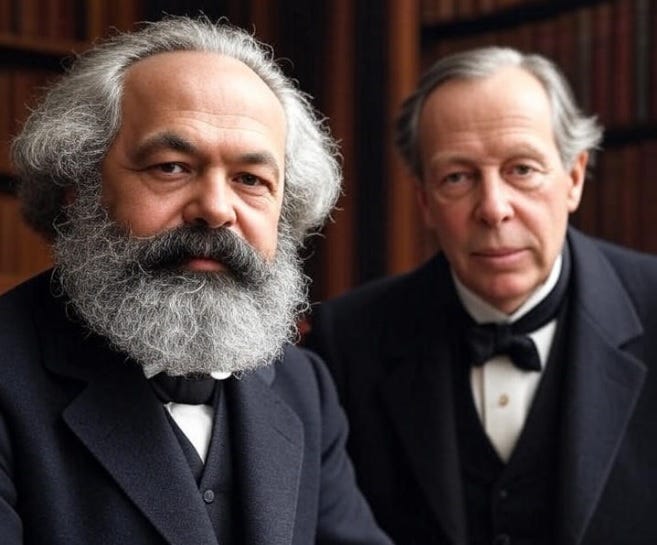

Elected to Parliament during the Europe-wide revolutionary “Crazy Year” of 1848, Rothschild refused to swear a Christian oath. Sustained Jewish advocacy ultimately secured parliamentary approval of the Oath of Abjuration Bill, known as the “Jew Bill,” in 1858, enabling Rothschild to serve as an MP. Shortly thereafter, his Jewish protégé from the Conservative Party, Benjamin Disraeli, returned to the cabinet and, in 1868, became prime minister.

Image: Disraeli, the first person caricatured in the London magazine Vanity Fair, 30 January 1869. Source Wikipedia.

Historian Niall Ferguson observes that Benjamin Disraeli, in his novels Coningsby (1844), Sybil (1845) and Tancred (1847) celebrated Lionel Rothschild and his wife, Charlotte:

Another Rothschildian passage has Eva ask Tancred: “Which is the greatest city in Europe?” “Without doubt, the capital of my country London.” ... “How rich the most honoured man must be there! Tell me, is he a Christian?” “I believe he is one of your race and faith.” “And in Paris; who is the richest man in Paris?” “The brother, I believe, of the richest man in London.” “I know all about Vienna,” said the lady, smiling, “Caesar makes my countrymen barons of the empire, and rightly, for it would fall to pieces in a week without their support.”

Where Disraeli diverged from Charlotte was in his provocative—and to contemporaries, scandalous—assertion that, in “supply[ing] the victim and the immolators” at Christ’s crucifixion, the Jews had “fulfilled the beneficent intention” of God and “saved the human race.” Nor would she likely have endorsed his claim in Sybil (1845) that “Christianity is completed Judaism, or it is nothing. ... Judaism is incomplete without Christianity." (The House of Rothschild, pp. 82-83.)

Ferguson also notes that in Coningsby (1844), Disraeli openly addresses Jewish influence:

When Disraeli seeks to illustrate his point about the extent of Jewish influence, he draws with extraordinary directness from recent Rothschild history when he has Sidonia say: “I read of peace and war in newspapers, but I am never alarmed, except when I am informed that the Sovereigns want more treasure. A few years back we were applied to by Russia. Now, there has been no friendship between the Court of St Petersburgh and my family. It has Dutch connections, which have generally supplied it; and our representations in favour of the Polish Hebrews, a numerous race, but the most suffering and degraded of all the tribes, have not been very agreeable to the Czar. However, circumstances drew to an approximation between the Romanoffs. … So you see my dear Coningsby, that the world is governed by very different personages from what is imagined by those who are not behind the scenes.” ...

Hannah Barent Cohen-Rothschild wrote to her daughter, Charlotte: “in dwelling upon the good qualities of Sidonia’s race; in using many arguments for their emancipation he cleverly introduced many circumstances we might recognise and the character was finely drawn ... I have written a note to him expressing our admiration of his spiritual production. (The House of Rothschild, p 80-81.)

Most probably also Marx had read Disraeli’s books and was very proud of both the Rothschilds and Disraeli. In fact, so proud that the only time in his life he let slip his true Jewish feelings was in a reference to Disraeli. Daniel Schwarts notes this when reviewing Shlomo Avineri’s book Karl Marx: Philosophy and Revolution:

Avineri appears to presume that Marx’s lifelong silence on the matter of his Jewish origins—broken only once when, in a letter to his Dutch uncle (likewise converted), he referred to Benjamin Disraeli as “our fellow tribesman”—speaks volumes about the degree to which his ancestry lurked in his consciousness. (Daniel B. Schwartz. Marx and the Jewish Fingerprint Question. 2020)

Few contrasts are starker than those between Russia, where Jews faced stringent restrictions, and Britain, where a Jew could mock Christianity, boast of enormous Jewish influence, and, with Rothschild support rise in the Conservative Party and finally become prime minister. Unsurprisingly, Karl Marx championed the British Empire while condemning the Russian Empire. But his Jewish pride and Russophobia were further amplified by a distinct racialist ideology. In 1884, a year after Marx’s death, partly based on Marx’s notes Friedrich Engels published The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, asserting that superior nutrition among Aryans and Semites during pastoral eras “may, perhaps, explain the superior development of these two races” (p. 22, 1893 ed.).

Erik van Ree’s Marx and Engels’s Theory of History: Making Sense of the Race Factor (2002) demonstrates that Marx shared Engels’ racialist views, endorsing a hierarchy that placed Jews and Germanic peoples above Slavs, Blacks, and Asiatic populations. Jews and Germanic peoples were considered more adept at advancing production. Such racial hierarchies, prevalent in the 19th century, underpinned Marx and Engels’ markedly disparaging view of Slavs, particularly Russians. Marx supported Franciszek Henryk Duchinski’s claim that Russians were not Slavs or part of the “Indo-Germanic race” but rather Mongols and Finns. He further posited that Russian soil “Tartarizes” Slavs. Marx and Engels went so far that they even deemed the Balkan Slavs unfit for progress, outrageously regarding the Turks as “most competent to hold supremacy.”

Revolutionary geopolitics: British vs. Russian imperialism

Marx's racialist philosemitic views coincided strikingly with his deep-seated antipathy toward Slavs and Russians, whom Jewish and Muslim slave traders had targeted for centuries. They also aligned with his perception of the British Empire as the spearhead of a coalition against Russia. Indeed, Marx so admired the British Empire that, in his 1853 New-York Daily Tribune articles The British Rule in India and The Future Results of British Rule in India, he defends British imperialism as a catalyst for progress, even portraying it as “a tool of history.”

Marx's own family had probably also played a role in the defence of the British Empire. One important reason why the Rothschilds had formed a dynastic alliance with the Barent-Cohens was the latters unparalleled Jewish elite connections, trade routes, and intelligence web across Europe and especially in Britain and Netherlands. Barent-Cohen-Rothschild network enabled covert transfers of funds from London to European allies, largely via Dutch channels, to finance anti-Napoleonic coalitions. Nanette Cohen and her husband, Isaac Pressburg, a descendant of Nijmegen’s rabbinic leaders in a strategic Dutch-German border town, likely played a role in these operations, bolstering the Rothschilds’ geopolitical ambitions. Marx’s refusal to write a lucrative biography or memoir, despite severe financial difficulties, probably arose from concerns that such accounts would spark scrutiny of his Jewish elite ancestors and networks.

Herbert H. Kaplan notes that without the help of the Rothschilds Wellington might not have been able to fight the French efficiently.

Using funding from his father to make initial purchases, he employed experienced smuggler seamen to transport the cargoes across the Channel, and with his younger brother, James, organized a network of merchants, dealers, and bankers on the Continent to sell his specie and bullion. Nathan grossed millions of English pounds sterling from these transactions and, for as long as the war continued and the market price of gold and silver remained well above their Mint prices, he could have looked forward to a comfortable income.

But the most significant opportunity for Nathan arose—and his importance in history became assured—when the desperate British government recognized that his skills and network were what it needed to supply large amounts of French specie to Wellington to pursue the war against Napoleon in France. He accomplished this commission by mobilizing his brothers and staff to fan out across Europe to purchase, collect, and deliver more than one million French coins to Wellington in the south of France. Given that Wellington had threatened not to pursue the war unless he received the money he demanded, it can be said that the efforts by the Rothschilds were as crucial to the defeat of Napoleon as any battle that was fought. (Herbert H. Kaplan. Nathan Mayer Rothschild and the Creation of a Dynasty. The critical years 1806–1816. (2006) p. 175-176)

The Rothschilds and their Jewish network played a significant role in Napoleon’s defeat. Consequently, they felt deeply betrayed when after the Napoleonic Wars The Holy Alliance led by Russia reintroduced many restrictions on Jews. Marx’s own family experienced this painfully when it was semi-forced to convert. The Jews, particularly the Marx family, had an ax to grind.

Over three decades, the Rothschild-led Jewish intelligence networks worked to support liberal change in continental Europe. Then finally came the “Crazy Year” of 1848, when Europe was swept by liberal revolutions promising Jewish emancipation. Naturally, Marx played a role in these revolutions with his Communist Manifesto and various revolutionary activities. However, just as the revolutions seemed poised to succeed, they were suppressed by the political and military intervention of the Russian Tsar, Nikolai I. His military support for conservative regimes, notably Austria, crushed revolutions in Hungary and Italy, preserving the geopolitical order.

The Tsar’s conviction in his role as guardian of this conservative— or, as Jews labeled it, ‘antisemitic’—order, bolstered by Russia’s restrictive Jewish policies, made him a prime target for Jewish efforts to overthrow him.

Image: Gendarme of Europe, Nicholas I.

The Rothschilds and other Jews now had to create a grand alliance against Russia. It was essential to enlist Britain to lead this alliance due to its vast navy and financial power. This was a formidable task for several reasons. First, Britain was a monarchy with the largest revolutionary proletariat. Why should it support revolutionary movements abroad, especially since they could easily spread to Britain? The Rothschilds presumably convinced Britain that Jewish networks could assist British intelligence in manipulating revolutionary forces to topple only governments hostile to Britain. Such an arrangement would have granted British intelligence greater influence over other countries and protection against its own British revolutionaries.

But why should Britain undermine and topple other governments at all? Would that not disrupt the balance of power achieved after decades of Napoleonic wars? Here, the Jews had to invoke the specter of danger: the Tsar was intent on expanding his empire and had to be stopped before seizing the Turkish straits! This raised another awkward question: Was Britain not also expanding its empire? Did it not control the ever expanding global empire including also in Mediterranean Gibraltar and Malta and aspire to control the Suez and build a canal? Furthermore, why would a Christian country support a Muslim empire that regularly massacred thousands of Christians in the Balkans and enslaved Christians? Was Britain not opposed to massacres, slavery and the slave trade?

The politically rational approach for Britain would have been to maintain the balance of power by negotiating spheres of influence with Russia, protect Christian values and culture, limit revolutionary activity in Europe while allowing gradual change, free the Balkans, end slavery, and possibly partition the Muslim Ottoman Empire. However, this did not suit the Rothschilds, as it would have yielded little profit and left the conservative “anti-semitic” order intact. Liberal revolutions, military build-ups and limited wars were far more lucrative and allowed Jews to play states against each other and pressure conservative monarchs to grant privileges and emancipation. Abandoning the Muslim Ottoman Empire was also opposed because it had sustained a centuries-long alliance with Jewish communities, often opposing Christian powers, with many Jews such as Sassoons occupying prominent roles within the Empire.

Following the Napoleonic Wars, British foreign policy became increasingly Russophobic. After the revolutionary upheavals of 1848, this sentiment intensified, culminating in a British-French-Ottoman alliance determined to defeat Tsar Nicholas I in the Crimean War. Unsurprisingly, Marx emerged as a vocal critic of Russia and an ardent advocate for the Crimean War, denouncing Russia as a “barbaric” power. During the Crimean War Marx claimed that Russia could be defeated. What Charles XII and Napoleon started should be finally finished:

Not that we think ‘Holy Russia’ unassailable. On the contrary, Austria and Prussia united are quite able, if merely military chances are taken into account, to force her to an ignominious peace. … The strategy of an attack upon Russia from the west has been clearly enough defined by Napoleon, and had he not been forced by circumstances of a non-strategic nature to deviate from his plan, Russia’s integrity would have been seriously menaced in 1812. (Karl Marx. New York Tribune, 1 January 1855.)

Prussian King Frederick William IV’s neutrality, aligning with Russia, prevented the Tsar’s overthrow, dealing a blow to the Rothschild-backed coalition. This setback underscored the need for a broader anti-Russian alliance encompassing Prussia. Consequently, post-Crimean War, the Rothschilds prioritized intelligence networks, enhancing the strategic importance of Karl Marx’s connections to multiple intelligence networks.

Revolutionary Practice: Jewish Intelligence Networks

The Rothschilds were renowned for their private intelligence network, leveraging ancient Jewish intelligence systems and utilizing Jewish merchants, bankers, and community leaders across Europe. The Marx family, through the Pressburgs and Henriette’s sister Sophia’s marriage to Lion Philips, was likely part of this Rothschild intelligence network. Lion was a converted Jew and a tobacco industrialist with great wealth. His son Friedrich became a banker and also the founder of the famous Philips company. Lion's daughter Antoinette became a communist taking also part in the First Socialist International. All three actively helped Marx in his communist career both financially and organizationally. The Philips family were probably also part of the Rothschild intelligence network.

Marx’s connection to British intelligence was likely facilitated through his close friend, Friedrich Engels, whose family owned cotton mills not only in Cologne, Prussia but also Manchester, Britain granting him access to both Prussian and British industrial and political elites. Engels’ detailed knowledge of economic and military affairs, shared in their correspondence, suggests he relayed Marx’s insights on revolutionary movements to authorities, aligning with their anti-Russian goals.

Engels background as an industrialist made him highly suspicious. Why would an industrialist support communists unless he was somehow sabotaging and neutralizing them? Engels was well aware how many communists were suspicious of him. McLellan explains:

In 1865, as Marx and Engels were breaking with Lassalle’s successor, Johann Baptist von Schweitzer, Engels warned Marx that Schweitzer’s followers would say, “What does that Engels want, what has he been doing all these years, how can he speak in our name & tell us what we should do, the guy sits in Manchester and exploits the workers, etc.” (McLellan, David. 2006. Karl Marx: A Biography. p. 380.)

Wolfgang Waldner’s Der Preußische Regierungsagent Karl Marx (2009) argues that Marx’s connection to Prussian intelligence was likely facilitated through his wife, Jenny von Westphalen, who came from a prominent Prussian aristocratic family with deep ties to the Prussian bureaucracy, rooted in their elite ancestry. Her father, Ludwig von Westphalen (1770–1842), a liberal Prussian civil servant in Trier, descended from Scottish nobility through his mother and Brunswick nobility through his father, who served as chief of staff to the Duke of Brunswick during the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). Ludwig’s access to elite networks positioned him within trans-European intelligence networks, including those linked to the Rothschilds.

Ludwig became a close friend of Karl Marx’s father, Heinrich Marx in Trier before the latter’s conversion to Lutheranism (1816–1817). Suspicions suggest Ludwig encouraged Heinrich’s conversion by promising connections to Prussian and British elites, protection from antisemitic restrictions, and potential intelligence work for anti-Russian strategies. Ludwig’s mentorship of Karl Marx, fostering his intellectual development and introducing radical ideas, further tied the Marx and Westphalen families together. As a key figure, Ludwig facilitated their integration into a broader intelligence community working to form a British-Dutch-Prussian front against Russia, leveraging his noble ancestry to access high-level networks.

Ludwig’s children strengthened these intelligence networks. His son, Ferdinand von Westphalen (1799–1879), Jenny’s half-brother from his first marriage to Elisabeth von Veltheim, was a highly conservative and reactionary Prussian official who served as the Prussian Minister of the Interior from 1850 to 1858, a period marked by intense repression of revolutionary movements following the 1848 uprisings and overlapping with the Crimean War. As Interior Minister, Ferdinand oversaw Prussia’s police, surveillance, and intelligence operations, including the monitoring of radicals like Marx, who was expelled from Prussia in 1849. Despite their ideological opposition, Ferdinand’s position made him a powerful conduit for Marx’s intelligence activities. Waldner argues Marx leveraged Ferdinand’s high-ranking role to infiltrate socialist movements and steer them in directions favorable to Prussian interests, such as suppressing internal revolutions while focusing unrest on Russia, aligning with the goal of integrating Prussia into a new anti-Russian coalition.

Jenny’s full brother, Edgar von Westphalen (1819–1885), a lifelong friend and schoolmate of Marx in Trier, was a communist politician and early member of the Brussels Communist Correspondence Committee (1846) and the Communist League. Despite his radical credentials, Edgar is suspected of being closely connected to Prussian intelligence, possibly acting as an informer within socialist circles. His ability to travel freely, including immigrating to Sisterdale, Texas, in the 1840s as part of the Adelsverein-sponsored German settlement, fighting for the Confederacy in the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865), and later returning to Berlin with support from Ferdinand, suggests protection by Prussian authorities. Edgar’s activities in the U.S., particularly in Texas, a hub for German immigrants and Confederate networks, raise suspicions of connections to early Prussian or American intelligence networks, possibly facilitated by German-American political networks or Prussian diplomatic channels linked to Ludwig’s British contacts. Waldner implicates Edgar as a secondary agent in Marx’s Prussian intelligence network, with his U.S. activities potentially monitoring transatlantic radical movements to serve Prussian or broader anti-Russian interests.

Karl Marx was distinctively positioned among multiple dynastic intelligence networks: the Rothschild-Jewish network through his Jewish relatives, including the Pressburgs, and Philipses; the Prussian networks via his wife’s Westphalen family (Ludwig, Ferdinand, Edgar); and the British network through Friedrich Engels. This strategic positioning enabled Marx to evade imprisonment despite his revolutionary activities and to operate with considerable autonomy within the intelligence sphere. However, Marx was not merely a Rothschild, British, or Prussian agent but served as an ideological and geopolitical operative, seeking to forge a British-led coalition against Russia to overthrow the antisemitic Tsar, thus unleashing revolutionary forces to establish a communist society. His racialist worldview, which exalted Jews and Germanic peoples while disparaging Russians and Slavs, and his eschatological vision of transforming reality through violent revolution, reinforced this anti-Russian focus. By restraining revolutionary activity in Britain and Prussia/Germany, Marx likely sought to stabilize these nations, bolstering their capacity to confront Russia, possibly through a conflict akin to the Second Crimean War.

Revolutionary Strategy: Marx vs. Bakunin

Karl Marx’s political behavior was so contradictory—defending British imperialism while fixating on Russia—that it was inevitable that someone would notice. Indeed, one of Marx’s early friends and collaborators, Mikhail Bakunin, did so. The contrast between these two men—Jew and Russian, communist and anarchist—was stark. Marx sought to establish freedom from above by seizing state power, whereas Bakunin advocated freedom from below by dismantling the state. Bakunin urged revolutions across Europe, particularly in Britain and Prussia/Germany, leveraging their growing working classes, while Marx resisted revolutionary action there, favoring gradual political reform and promoting revolutions in Russia instead.

Image: Marx and Bakunin

This divergence fostered opposing geopolitical perspectives. Bakunin viewed Britain and Germany, with their efficient states and propaganda, as the greatest threats to freedom, whereas Marx identified autocratic Russia and its anti-revolutionary policies as the primary obstacle. These irreconcilable political and strategic visions led to the dissolution of the First Socialist International when Marx expelled Bakunin’s faction, further straining their once-close relationship. Bakunin began to assert, or at least strongly imply, that Jews were dominating the Socialist International to bolster the relatively philo-Semitic governments of Britain and Germany.

In Statism and Anarchy (1873), Bakunin accused Marx of aspiring to dictatorship.

According to Marx’s theory, however, the people not only must not destroy it, they must fortify it and strengthen it, and in this form place it at the complete disposal of their benefactors, guardians, and teachers – the leaders of the communist party, in a word, Marx and his friends, who will begin to liberate them in their own way. They will concentrate the reins of government in a strong hand, because the ignorant people require strong supervision.

They will create a single state bank, concentrating in their own hands all commercial, industrial, agricultural, and even scientific production, and will divide the people into two armies, one industrial and one agrarian, under the direct command of state engineers, who will form a new privileged scientific and political class. (p. 545.)

In his correspondence, Mikhail Bakunin explicitly linked communism to Jews and the Rothschilds. These letters, still untranslated into English and unavailable online, have spawned erroneous or low-quality translations, paraphrased quotations, and fabrications that undermine credibility. Libcom translations of Bakunin’s writings also come with a warning:

libcom note: needless to say, the writing which follows is completely abhorrent, not to mention full of complete fabrications, racist conspiracy theories, falsehoods, etc. It is reproduced for historical reference only. Similarly, many other historical revolutionaries like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels also held abhorrent and racist views.

To the Companions of the Federation of International Sections of Jura

February-March 1872

Brothers and friends!

… The Jews today form a real power in Germany. For a long time now, they have been sovereign masters in the banking business. But in the last thirty years or so, they have also succeeded in a kind of monopoly in literature - there is hardly a newspaper in Germany that does not have its own Jewish editor, and Journalism and Banking join hands, rendering each other valuable services.

It is a very interesting race, the race of the Jews! a forced emigration. And it was in the midst# |4 of this emigration that the cult of Jerusalem, the symbol of national unity, was formed and deepened in the hearts of the Jews, Nothing so unites as misfortune.

Dispersed and scattered throughout Asia, enslaved, despised, oppressed, but always intelligent, they formed more than ever a nation: the international nation of Asia and part of Africa. Torn from the land Jehovah had given them and no longer able to devote themselves to agriculture, they must seek another outlet for their passionate [intercalated: and] restless activity. This outlet could be none other than Trade; and thus the Jews became the trading people par excellence. In all countries they found their countrymen, victims like themselves of foreign oppression, despised, persecuted like themselves, and like themselves animated by a natural and deep-seated hatred against the conquering nations. This explains how in the long run there must have been formed among all the Jewish tribes scattered over Asia and Africa, among the Jews of all , a vast trading association, of mutual help and assistance, and of joint exploitation of all foreign nations; a people of parasites living on the sweat and blood of their conquerors.

Whatever the value of that translation Bakunin did also strongly suggests in Statism and Anarchy that Jews were problematic, portraying Wilhelm Liebknecht—who had a Jewish wife and half-Jewish children—as Karl Marx’s instrument: “This was the German Social-Democratic Workers’ Party. It was headed by two very talented men, one a semi-worker, the other a writer and direct disciple and agent of Marx: Bebel and Liebknecht.” (p. 544)

Bakunin prophetically cautioned Russians and other Slavs against joining Marxists, deeming it suicidal:

Therefore we will refrain from urging our Slavic brothers to join the ranks of the Social Democratic Party of the German workers, which is led first and foremost by Marx and Engels in a kind of duumvirate vested with dictatorial power, with Bebel, Liebknecht, and a few Jewish literati behind them or under them.

On the contrary, we must exert all our efforts to dissuade the Slavic proletariat from a suicidal alliance with this party, which is in no way a popular party but in its orientation, objective, and methods is purely bourgeois and, furthermore, exclusively German, that is, lethal to the Slavs. (p. 222.)

Conclusion: Marx’s Hidden Legacy and the Crimean War

Karl Marx’s revolutionary ideology, rooted in his Jewish elite heritage, transcended his public persona as a communist theorist. His unique position between Jewish and Gentile intelligence networks allowed him to operate as an ideological and geopolitical agent, true to his communist vision while protecting Rothschild and British interests and advancing anti-Russian goals through political, racialist and eschatological justifications.

Historians’ deliberate omission of Marx’s Jewish pride, resentment, vengeful motives, Satanic poetic imagery, radical eschatological visions, racialized ideological convictions, and Jewish geopolitical alignment obscures a critical truth: his Jewish elite heritage, values, and intelligence networks shaped his mission to eradicate antisemitism and capitalism through a universal Jewish-led revolution and dictatorship, intricately linked to the Crimean War era’s Jewish geopolitical objectives, which persist covertly even today.

References:

Mikhail Bakunin. 1873. Statism and Anarchy.

https://libcom.org/article/translation-antisemitic-section-bakunins-letter-comrades-jura-federation

Berlin, Isaiah. 1996. Karl Marx: His Life and Environment.

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.54900/mode/2up

Engels, Friedrich. 1893. The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State.

https://archive.org/details/originoffamilypr00fred/page/22/mode/2up?q=superior+development

Ferguson, Niall. 1998. The House of Rothschild.

https://ia903409.us.archive.org/33/items/the-house-of-rothschild-ferguson-niall/The%20House%20of%20Rothschild%20-%20Ferguson%2C%20Niall.pdf

Hoppe, Hans-Hermann. 1990. “Marxist and Austrian Class Analysis.” Journal of Libertarian Studies.

https://mises.org/journal-libertarian-studies/marxist-and-austrian-class-analysis

Herbert H. Kaplan. Nathan Mayer Rothschild and the Creation of a Dynasty the critical years 1806–1816. (2006)

https://books.google.com.ph/books/about/Nathan_Mayer_Rothschild_and_the_Creation.html?id=khxKMg6wjH4C&redir_esc=y

Kengor, Paul. 2020. The Devil and Karl Marx: Communism’s Long March of Death, Deception and Infiltration.

https://ia600600.us.archive.org/31/items/hybridphilosophy-collection/The-Devil-and-Karl-Marx-Paul-Kengor.pdf

Marx, Karl. 1843. On the Jewish Question.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/jewish-question/

Marx, Karl. 1848. The Communist Manifesto.

https://gutenberg.org/ebooks/61

Marx, Karl. 1853a. “The British Rule in India.” New-York Daily Tribune, June 25.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1853/06/25.htm

Marx, Karl. 1853b. “The Future Results of British Rule in India.” New-York Daily Tribune, August 8.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1853/07/22.htm

Marx, Karl. 1855. “Russia Articles.” New-York Daily Tribune, January 1.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/subject/russia/crimean-war.htm

Marx, Karl. 1867–1894. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume I (1867)

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/index.htm;

Volume II (1885)

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1885-c2/index.htm;

Volume III (1894)

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1894-c3/index.htm

McLellan, David. 2006. Karl Marx: A Biography.

https://archive.org/details/karl-marx-his-life-and-thought/mode/2up

Raico, Ralph. 1978. Classical Liberal Roots of the Marxist Doctrine of Classes. Mises Daily.

https://mises.org/mises-daily/classical-liberal-roots-marxist-doctrine-classes

Al Raven. 2021. Translation of the antisemitic section of Bakunin's "Letter to Comrades of the Jura Federation".

https://libcom.org/article/translation-antisemitic-section-bakunins-letter-comrades-jura-federation

Rothbard, Murray. 1988. “Karl Marx as Religious Eschatologist.” Mises Daily.

https://mises.org/mises-daily/karl-marx-religious-eschatologist

Rothschild Archive. 2025. “Rothschild Family Tree.”

https://www.rothschildarchive.org/genealogy/

Schwartz, Daniel B. 2020. “Marx and the Jewish Fingerprint Question.” Jewish Review of Books, Spring.

https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/articles/7219/marx-and-the-jewish-fingerprint-question/#

Shahak, Israel. 1994. Jewish History, Jewish Religion: The Weight of 3000 Years.

https://archive.org/details/JewishHistoryJewishReligionTheWeightOf3000Years

Sperber, Jonathan. 2013. Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life.

https://archive.org/details/karlmarxnineteen0000sper/mode/2up

van Ree, Erik. 2002. “Marx and Engels’s Theory of History: Making Sense of the Race Factor.” Journal of Political Ideologies.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13569317.2019.1548094#d1e244

Waldner, Wolfgang. 2009. Der Preußische Regierungsagent Karl Marx.

https://archive.org/details/bod-marx/mode/2up; https://www.wolfgang-waldner.com/der-marx-engels-schwindel/

Wurmbrand, Richard. 1976. Marx and Satan.

https://archive.org/details/MarxAndSatanRichardWurmbrand1976_201904