Rationalist Grand System vs. Ruling Elite

Rationalist foundations of paleolibertarianism summarized with diagrams

As with most ideological frameworks, paleolibertarianism lacks a singular, definitive description. At one extreme, it is viewed as a strategic alliance uniting conservatives and libertarians against state overreach. At the other, it represents a profound effort to refine and expand the philosophical and practical foundations of libertarianism. This article explores the latter interpretation, drawing on the works of Murray Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Ralph Raico, David Gordon, Gary North, Guido Hülsmann, Stephan Kinsella, and Lew Rockwell.

Paleolibertarianism seeks to systematically advance libertarianism by grounding it in a rigorous philosophical framework, from which it deduces precise meanings of non-aggression and liberty.

1. Rationalism

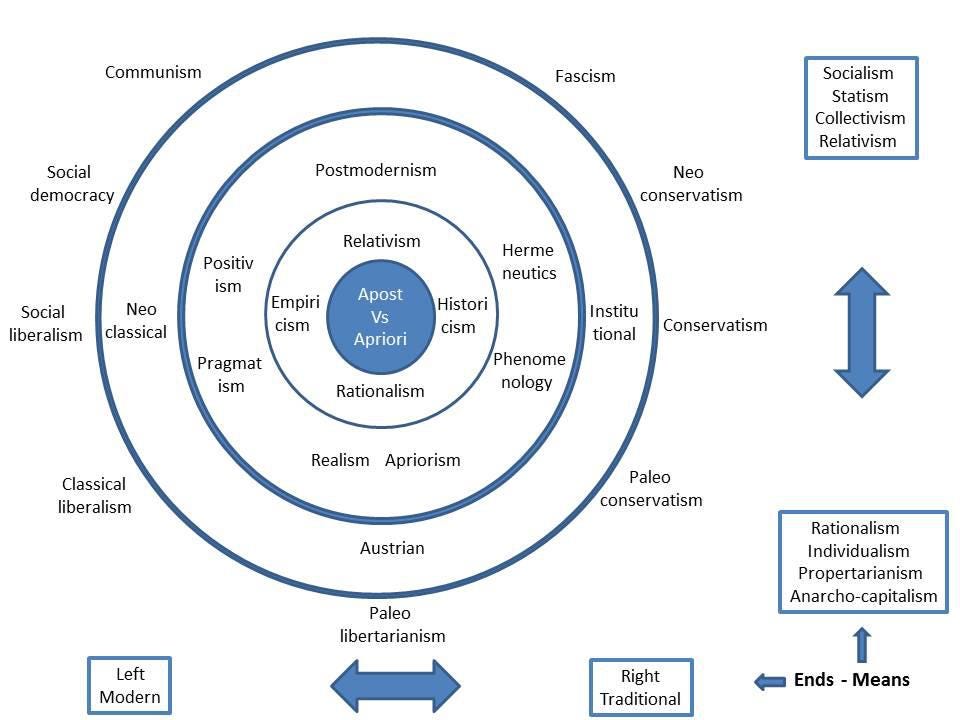

Among libertarians, there is no consensus on the philosophical underpinnings of their ideology. Some embrace rationalism, others empiricism, and a few even postmodernism. Rationalists typically align with the Austrian School, often associated with the Mises Institute, while empiricists gravitate toward the Chicago School, linked to the Cato Institute—both considered libertarian strongholds.

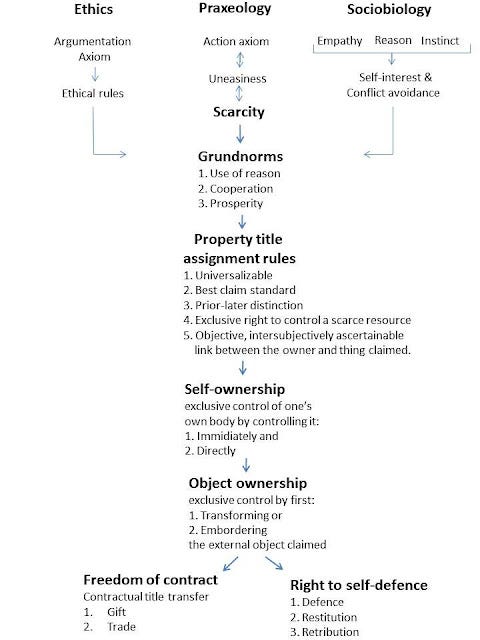

Paleolibertarians, firmly rooted in the Austrian School, advocate for pure, extreme rationalism, where all reasoning and action must derive from first axiomatic principles. Praxeology provides the foundation with its axiom of human action, which posits that humans act purposefully. Any attempt to refute this axiom inherently affirms it, as disputation itself is a purposeful act.

From this axiom of action, pure rationalism constructs a comprehensive Radical Austrian Grand System, methodically progressing from praxeology to philosophy, ethics, economics, politics, and history. Hans-Hermann Hoppe explains:

Rothbard is the latest and most comprehensive system-builder within Austrian economics. Only among rationalists does a constant desire for system and completeness exist. While they contributed much to its foundation, neither Menger nor Böhm-Bawerk accomplished this ultimate intellectual desideratum. This feat was accomplished only by Mises, with the publication of his monumental Human Action. “Here at last,” Rothbard wrote about Human Action, “was economics whole once more, once again an edifice. Not only that—here was a structure of economics with many of the components newly contributed by Professor Mises himself.” ….

Since then, only Rothbard has accomplished a similar achievement with the publication of Man, Economy, and State and its companion volume, Power and Market. … Yet, Rothbard’s achievements go far beyond his innovations in economic theory. They go far beyond even his accomplishment of integrating these innovations into a grand, comprehensive and unified system of Austrian economics. Although an economist by profession, Rothbard’s work encompasses also political philosophy (ethics) and history.

Unlike the utilitarian Mises, who denied the possibility of rational ethics, Rothbard recognized the need for an ethical system to complement value-free economics so as to make the case for the free market truly watertight. Drawing on the theory of natural rights, in particular on the work of John Locke, and on the genuinely American tradition of anarchistic thought of Lysander Spooner and Benjamin Tucker, Rothbard developed a system of ethics based on the principles of self-ownership and the original appropriation of un-owned natural resources through homesteading. Any other proposal, he demonstrated, either does not qualify as an ethical system applicable to everyone qua human being, or it is not viable, for following it would literally imply death while it requires a surviving proponent, and thus leads to performative contradictions. …

In The Ethics of Liberty, his second magnum opus, Rothbard deduced the entire corpus of liberal-libertarian law—from the law of contracts to the theory of punishment—from these first axiomatic principles; and in his For a New Liberty, he applied this ethical system to a diagnosis of the present age and the proposal, and economic analysis, of the political reforms necessary to achieve a free and prosperous commonwealth.

Furthermore, although first and foremost a theoretician, Rothbard was also an accomplished historian, and his writing contains a wealth of empirical information rarely matched by any empiricist or historicist. In fact, it is Rothbard’s recognition of economics and political philosophy (ethics) as pure aprioristic theory, and of theoretical reasoning as logically anteceding and constraining every historical investigation, which makes his empirical scholarship superior to that of most orthodox historians, and has established him as one of the outstanding “revisionist” historians. 1

Murray Rothbard and, in particular, Hans-Hermann Hoppe categorized philosophy into three schools—rationalism, empiricism, and historicism—though a fourth school, pure relativism, which rejects the possibility of knowledge, could also be acknowledged. These philosophical schools naturally give rise to distinct schools of ethics, economics, and politics, thereby shaping corresponding political ideologies.

2. Non-Aggression Axiom (NAX)

While all libertarians endorse the non-aggression principle (NAP), they diverge on its ethical foundations, drawing from utilitarianism, natural law, or other theories.

Paleolibertarianism elevates the NAP to a non-aggression axiom (NAX), asserting that denying non-aggression results in a performative contradiction. Natural law, estoppel and argumentation ethic all note denying non-aggression results in a contradiction.

The very act of arguing, as I am doing now in favor of a private property ethic, presupposes that I have property rights in my body. If I did not, I would not be able to argue as I do. Anyone trying to deny this would have to argue against it, thereby implicitly admitting to self-ownership in order to even make the argument. Thus, denying self-ownership involves a performative contradiction. 2

3. Propertarianism

Libertarians also differ on the practical implications of the NAP, with some advocating minarchism and others anarcho-capitalism. Paleolibertarianism’s NAX provides clarity on the meaning of non-aggression. It leads to propertarianism, where rights stem from self-ownership of one’s body, and additional property can be acquired only through homesteading or voluntary contractual transfer. In this view, human rights are synonymous with private property rights.

The NAX naturally entails anti-statism, viewing the state as an exploitative, mafia-like parasitic entity. It supports anarcho-capitalism and a private law society based on voluntary interactions. Disputes are minimized through covenant communities and resolved via propertarian arbitration. Hoppe explains:

The objective for a human ethic or a theory of justice, then, is the discovery of such rules of human conduct that make it possible for a—indeed, any—bodily person to act—indeed, to live his entire active life—in a world made up of different people, a “given” external, material environment, and various scarce—rivalrous, contestable or conflict-able—material objects useable as means toward a person’s ends, without ever running into physical clashes with anybody else.

Essentially, these rules have been known and recognized since eternity. They consist of three principal components. First, personhood and self-ownership: Each person owns—exclusively controls—his physical body that only he and no one else can control directly (any control over another person’s body, by contrast, is invariably an in-direct control, presupposing the prior direct control of one’s own body). Otherwise, if body-ownership were assigned to some indirect body-controller, conflict would become unavoidable as the direct body-controller cannot give up the direct control over his body as long as he is alive. Accordingly, any physical interference with another person’s body must be consensual, invited and agreed to by such a person, and any non-consensual interference with his body constitutes an unjust and prohibited invasion.

Second, private property and original appropriation: Logically, what is required to avoid all conflict regarding external material objects used or usable as means of action, i.e. as goods, is clear: every good must always and at all times be owned privately, i.e. controlled exclusively by some specified person. The purposes of different actors then may be as different as can be, and yet no conflict will arise so long as their respective actions involve exclusively the use of their own private property.

And how can external objects become private property in the first place without leading to conflict? To avoid conflict from the very start, it is necessary that private property be founded through acts of original appropriation, because only through actions, taking place in time and space, can an objective—intersubjectively ascertainable—link be established between a particular person and a particular object. And only the first appropriator of a previously unappropriated thing can acquire this thing as his property without conflict. For, by definition, as the first appropriator he cannot have run into conflict with anyone else in appropriating the good in question, as everyone else appeared on the scene only later. Otherwise, if exclusive control is assigned instead to some late-comers, conflict is not avoided but contrary to the very purpose of reason made unavoidable and permanent.

Third, exchange and contract: Other than per original appropriation, property can only be acquired by means of a voluntary—mutually agreed upon—exchange of property from some previous owner to some later owner. This transfer of property from a prior to a later owner can either take the form of a direct or “spot” exchange, which may be bi- or multi-lateral as when someone’s apples are exchanged for another’s oranges, or it may be unilateral as when a person makes a gift to someone else or when someone pays another person with his property now, on the spot, in the expectation of some future services on the part of the recipient. Or else the transfer of property can take the form of contracts concerning not just present but in particular also prospective, future-dated transfers of property titles.

These contractual transfers of property titles can be unconditional or conditional transfers, and they too can involve bi- or multi-lateral as well as unilateral property transfers. Any acquisition of property other than through original appropriation or voluntary or contractual exchange and transfer from a previous to a later owner is unjust and prohibited by reason. (Of course, in addition to these normal property acquisition rules, property can also be transferred from an aggressor to his victim as rectification for a previous trespass committed.) 3

Hans-Hermann Hoppe and Stephan Kinsella have further elucidated the basis of the propertarianism joining it with the theory of contract and retribution.

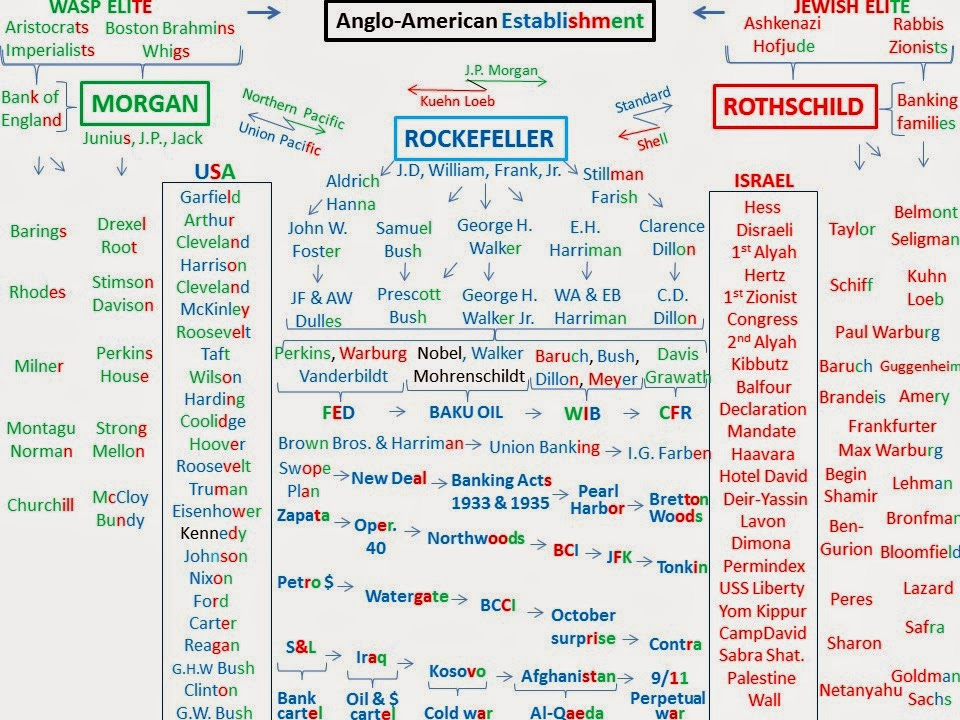

4. Ruling elite

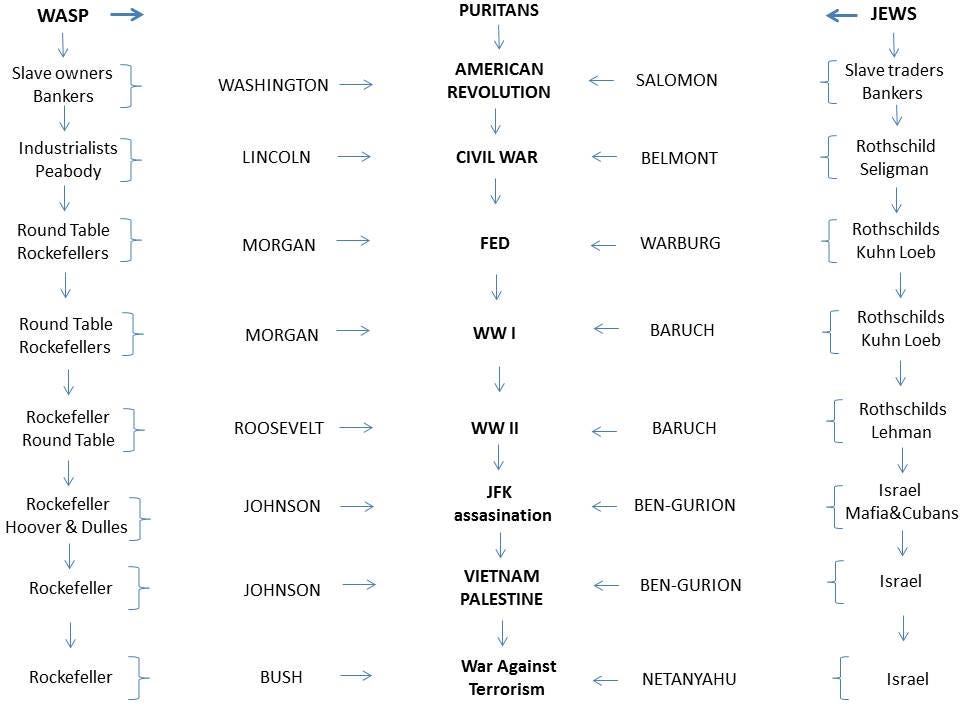

Paleolibertarians diverge from most libertarians not only in their anarchism, which views the state as a mafia-like entity, but also in their focus on the ruling elite controlling the state. They seek to unmask this elite, awakening the public to their exploitation through taxation, cartels, and fiat currency. Murray Rothbard categorized the ruling elite into three power blocs that have frequently collaborated to construct the state apparatus, particularly the Federal Reserve, yet often vied for dominance within the elite hierarchy.

5. Conservatism

Libertarians hold diverse views on values and social norms, ranging from liberalism to conservatism to nihilism. For paleolibertarians, liberty grounded in propertarianism is essential but insufficient for a flourishing society. Applying propertarianism practically requires accounting for empirical realities, including insights from evolutionary psychology. For instance, building free communities necessitates understanding differences in genetics and culture across individuals, sexes, generations, families, nations, races, and classes, particularly regarding IQ, time preference, personality types and ethnocentrism.

Is libertarian theory compatible with the worldview of the Right? And: Is libertarianism compatible with leftist views? As for the Right, the answer is an emphatic “yes.” Every libertarian only vaguely familiar with social reality will have no difficulty acknowledging the fundamental truth of the Rightist worldview. He can, and in light of the empirical evidence indeed must agree with the Right’s empirical claim regarding the fundamental not only physical but also mental inequality of man; and he can in particular also agree with the Right’s normative claim of “laissez faire,” i.e., that this natural human inequality will inevitably result also in unequal outcomes and that nothing can or should be done about this. 4

Traditional Western values and practices often reflect these empirical realities more effectively than modern ideologies. Paleolibertarians thus advocate respect for traditional Western culture, coupled with the principled discrimination and exclusion of those who threaten private property or these values. Private property inherently requires discrimination as a cornerstone of social organization, achievable through a network of propertarian covenant communities. Hoppe explains:

A member of the human race who is completely incapable of understanding the higher productivity of labor performed under a division of labor based on private property is not properly speaking a person… but falls instead into the same moral category as an animal – of either the harmless sort (to be domesticated and employed as a producer or consumer good, or to be enjoyed as a ‘free good’) or the wild and dangerous one (to be fought as a pest). …

One may say innumerable things and promote almost any idea under the sun, but naturally no one is permitted to advocate ideas contrary to the very covenant of preserving and protecting private property, such as democracy and communism. There can be no tolerance toward democrats and communists in a libertarian social order. They will have to be physically separated and removed from society. 5

However, covenant communities and their networks are not enough. Hoppe notes that it is also important to control borders.

Under the scenario of a natural order, then, it can be expected that there will be plenty of interregional trade and travel. However, owing to the natural discrimination against ethno-cultural strangers in the area of residential housing and real estate, there will be little actual migration, i.e., permanent resettlement. And whatever little migration there is, it will be by individuals who are more or less completely assimilated to their newly adopted community and its ethno-culture.6

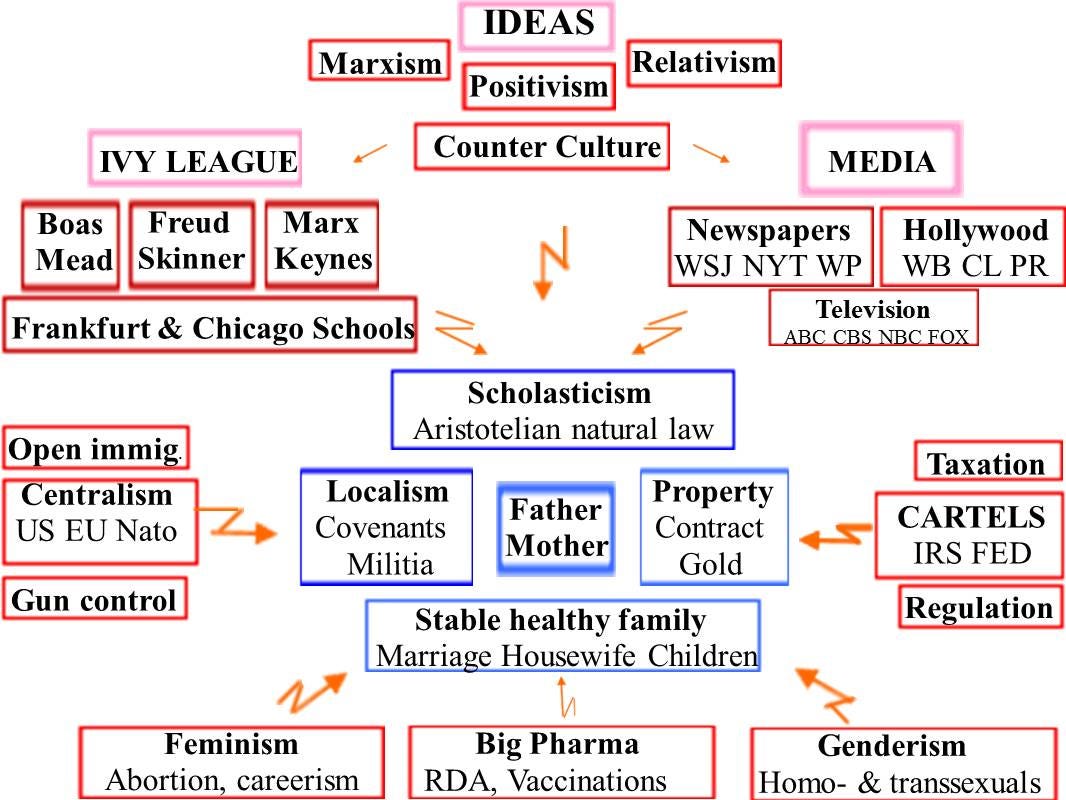

Paleolibertarians discern a systematic statist campaign by the ruling elite to undermine rationalism and propertarianism, aiming to erode individual liberty and the conservative family structure.

6. Revisionist History

Most libertarians subscribe to the Whig theory of history, viewing historical progress as a march from the aristocratic Dark Ages toward modern liberalism, parliamentary democracy, and freedom, exemplified by events like England’s Magna Carta, Glorious Revolution, American Revolution and Bill of Rights.

Paleolibertarians reject this narrative, seeing history as a regression from the relatively free aristocratic Middle Ages to increasingly statist liberal parliamentarism and, ultimately, global democratic communism. They regard the feudal Middle Ages as institutionally superior to the present era. Hoppe explains:

I only claim that this [feudal] order approached a natural order through (a) the supremacy of and the subordination of everyone under one law, (b) the absence of any law-making power, and (c) the lack of any legal monopoly of judgeship and conflict arbitration. And I would claim that this system could have been perfected and retained virtually unchanged through the inclusion of serfs into the system.” 7

Hoppe notes that the present modern democratic order is not only inferior but literally satanic:

[I]deal of social perfection is essentially also the one prescribed by the ten biblical commandments. Setting the first four commandments aside, which refer to our relation to God as the one and only ultimate moral authority and the final judge of our earthly conduct and the proper celebration of the Sabbath, the rest, referring to worldly affairs, display a deep and profoundly libertarian spirit. …

Indeed, the Middle Ages, notwithstanding its many imperfections, can be identified as a God-pleasing—a gott-gefaellige—social order, whereas the present democratic state order, notwithstanding its numerous achievements, stands in constant violation of God’s commandments and must be identified as a satanic order. To answer the question, then, Satan and his earthly followers will of course go all out to make us ignore and forget about God and belittle, besmirch, and denigrate everything and anything that shows His hand. …

Although many libertarians fancy an anarchic social order as a largely horizontal order without hierarchies and different ranks of authority—as “antiauthoritarian”—the medieval example of a stateless society teaches otherwise. Peace was not maintained by the absence of hierarchies and ranks of authority, but by the absence of anything but social authority and ranks of social authority. Indeed, in contrast to the present order, which essentially recognizes only one authority, that of the state, the Middle Ages were characterized by a great multitude of competing, cooperating, overlapping and hierarchically ordered ranks of social authority. 8

Many paleolibertarians view the British (1688) and American (1776) revolutions as catastrophic errors that paved the way for centralization and statism. United with conservatives in opposing revolution, they favor passive resistance, which avoids the escalating violence and statism inherent in revolutionary movements.

I did not celebrate the Fourth of July today. This goes back to a term paper I wrote in graduate school. It was on Colonial taxation in the British North American Colonies in 1775. Not counting local taxation, I discovered that the total burden of British imperial taxation was about 1% of national income. …

I will say it, loud and clear: The freest society on Earth in 1775 was British North America, with the obvious exception of the slave system. Anyone who was not a slave had incomparable freedom.

Jefferson wrote these words in the Declaration of Independence: “The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.”

I can think of no more misleading political assessment uttered by any leader in the history of the United States. No words having such great impact historically in this nation were less true. No political bogeymen invoked by any political sect as “the liar of the century” ever said anything as verifiably false as these words. …

In 1872, Frederick Engels wrote an article, “On Authority” He criticized anarchists, whom he called anti-authoritarians. His description of the authoritarian character of all armed revolutions should remind us of the costs of revolution.

“A revolution is certainly the most authoritarian thing there is; it is the act whereby one part of the population imposes its will upon the other part by means of rifles, bayonets and cannon — authoritarian means, if such there be at all; and if the victorious party does not want to have fought in vain, it must maintain this rule by means of the terror which its arms inspire in the reactionists.”

The revolutionaries are not remembered as treasonous. The victors write the history books.

What would libertarians — even conservatives — give today in order to return to an era in which the central government extracted 1% of the nation’s wealth? Where there was no income tax?

Would they describe such a society as tyrannical? 9

Paleolibertarians see all the revolutions and wars as stepping stones for the ruling elite to expand the power of the state.

7. Anti-War Stance

While libertarians generally oppose war, some support military interventions, particularly in support of Israel or Ukraine. Paleolibertarians, however, are unequivocally anti-war and anti-revolution, arguing that both lead to mass violence and entrench state power. Murray Rothbard explains:

[Libertarian] regards conscription as slavery on a massive scale. And since war, especially modern war, entails the mass slaughter of civilians, the libertarian regards such conflicts as mass murder and therefore totally illegitimate.10

Drawing on their analysis of the ruling elite, paleolibertarians identify two primary drivers of global conflict. First, the ruling elite seeks to eliminate nations that jeopardize their financial system, particularly the Federal Reserve and the dollar’s dominance. Second, the Jewish segment of the elite aims to neutralize countries that obstruct Jewish elite’s and Israel’s expansion and influence.

8. Paleostrategy

Paleolibertarians’ respect for conservative values and strategies fosters cooperation with conservatives against the state. This alliance is particularly viable when paleoconservatives, who share a commitment to traditional values, distance themselves from imperialist, neoconservative ideologies that prioritize foreign interventions. Lew Rockwell explains:

Libertarians can and must talk again with the resurgent paleoconservatives, now in the process of breaking away from the neocons. We can even form an alliance with them. Together, paleolibertarians and paleoconservatives can rebuild the great antiwelfare state, anti-interventionist coalition that thrived before World War II and survived through the Korean War. Together, we have a chance to attain victory. 11

Paleolibertarians believe that together with paleoconservatives they can awaken the public to recognize their exploitation by the ruling elite. This necessitates understanding that the ruling elite comprises both White and Jewish elites.

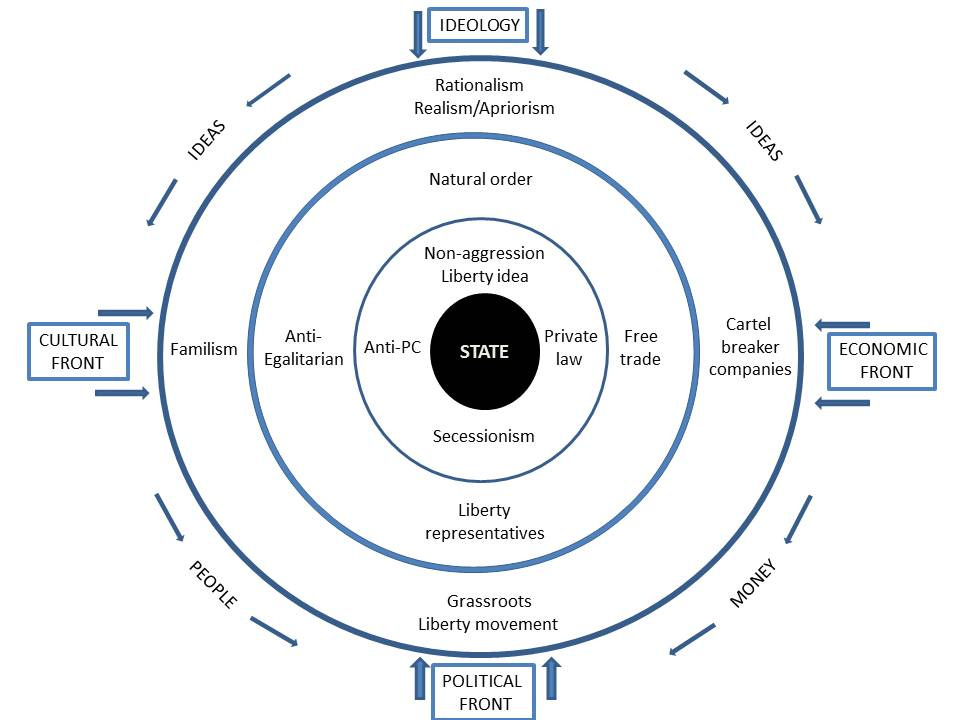

After understanding the nature of the state and ruling elite it is important to conduct a four-front attack against the state.

Conclusion

Regardless of one’s perspective on paleolibertarianism, it undeniably represents a meticulous effort to integrate libertarianism with the most radical and conservative traditions in philosophy, ethics, evolutionary psychology, revisionist history, culture, and strategy. By synthesizing these disparate methodologies into a cohesive Grand System, paleolibertarianism embodies the height of political incorrectness.

It boldly ventures into uncharted intellectual territory, challenging conventional libertarian thought. Whether one agrees with its tenets or not, paleolibertarians deserve recognition for sparking critical discussions on the foundations and applications of libertarianism.

Footnotes:

1. Hans-Hermann Hoppe. M. N. Rothbard: Economics, Science, and Liberty. Originally published in 15 Great Austrian Economists, ed. by Randall Holcombe (Auburn, Ala.: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1999), pp. 223–41.

https://mises.org/book/export/html/132679

2. Hans-Hermann Hoppe. The Economics and Ethics of Private Property, 2nd ed., p. 407. https://mises.org/library/book/economics-and-ethics-private-property

3. Hans-Hermann Hoppe. Foreword: Legal Foundations of a Free Society. Mises Wire 10/24/2023. Foreword to Stephan Kinsella’s, Legal Foundations of a Free Society (Houston, Texas: Papinian Press, 2023.

https://mises.org/mises-wire/foreword-legal-foundations-free-society )

4. Hans-Hermann Hoppe. Getting Libertarianism Right. Ludwig von Mises Institute 2018. p. 28.

https://mises.org/online-book/getting-libertarianism-right

5. Hans-Hermann Hoppe. Democracy: The God That Failed. (2001, Transaction Publishers) pp. 104, 218.

6. Hans-Hermann Hoppe. Natural Order, the State, and the Immigration Problem. (Journal of Libertarian Studies. Volume 16, no. 1. Winter 2002.)

https://cdn.mises.org/16_1_5.pdf

7. Hans-Hermann Hoppe. From Aristocracy to Monarchy to Democracy. Mises Institute 2014. p. 33.

https://mises.org/library/book/aristocracy-monarchy-democracy

8. Hans-Hermann Hoppe. The Libertarian Quest for a Grand Historical Narrative. Journal of Libertarian Studies 11/05/2020.

https://mises.org/journal-libertarian-studies/libertarian-quest-grand-historical-narrative

9. Gary North. Was the American Revolution a Mistake? Daily Reckoning July 4, 2024.

https://dailyreckoning.com/was-the-american-revolution-a-mistake-2/

10. Murray Rothbard. For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto. 2nd. ed. 1978.

https://mises.org/online-book/new-liberty-libertarian-manifesto

11. Rockwell, Llewellyn H. Jr. “The Case for Paleo-Libertarianism” (Liberty Magazine, January 1990, p. 38.

https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/5d62a0b2e3123d5d0247c5d5/5d9aad8de7a0b333dde9bbc0_Liberty_Magazine_January_1990%20pages%20Liberty%20-%20Page%2034%20-%20Liberty%20-%20Page%2038.pdf )